Trekking in Nepal a trip of a lifetime

Local Contributor

29 June 2025, 8:00 PM

By Carol Goddard

How would you choose to celebrate 25 years of wedded bliss?

Luxury cruise? Time at an island resort, basking in sun, sipping cocktails by the pool and snorkelling in clear, azure lagoons? Or perhaps heading off to bright city lights to enjoy a fine meal, a musical entertainment or a play?

For us, it was a no-brainer. We were looking for adventure. And so we chose to spend eight days in 1998, trekking in the Annapurnas in Nepal.

Eight days eating food mostly cooked on a kero burner, and tasting like it.

Eight days without washing, except for hands. Eight days of being caught in heavy rain while traversing swollen rivers, and sleeping in whatever clothes we were able to keep dry. Eight days of being bewitched by the most amazing scenery on the planet.

I got out my old photo album and trip notes recently, and quite predictably was instantly taken back to the sheer nerves, excitement but also the apprehension of what was to come, as we stepped off our plane in Kathmandu that first day.

We had never before attempted a trekking holiday in another culture, one so different from our own, and what a shock to the senses it initially was!

The noise, the gang of yelling, touting taxi drivers, the jostling, the craziness of that airport.

And then the chaos of the bus ride through the streets to our hotel, terrifying, but illuminating.

Buildings along the route appeared to be in a state of disrepair or totally derelict. Much later on in the trip we were to learn that this appearance was normal Nepali architecture.

The constant beeping of car horns, the seeming lack of any road rules, the choking car fumes, and the fearless pedestrians darting in and out of the traffic - all of this bid us welcome to Kathmandu.

Our hotel, a former palace surrounded by gorgeous manicured gardens, mercifully gave us the calmness we needed, accentuated by the delicate wafting of incense.

This was our first trip to a Third World country so everything was new and exciting, and a little overwhelming.

The Hotel Shanker was our haven on that first night. After a meet and greet with our fellow trekkers and a local Nepali restaurant dinner, we boarded a dubious looking bus at 5am the next morning, headed for Pokhara, and the start of our Annapurna trek.

The topography seen from the bus over those initial hours was intimidating to say the least. Our bus driver wound his way expertly around hairpin turns, higher and higher into the mountains, the dropoffs were scary to behold, and way down in the valleys below, the watercourses and rivers swirled with grey rapids.

This was the land we had come halfway across the world to walk through and experience. And so far, it was more than living up to expectations.

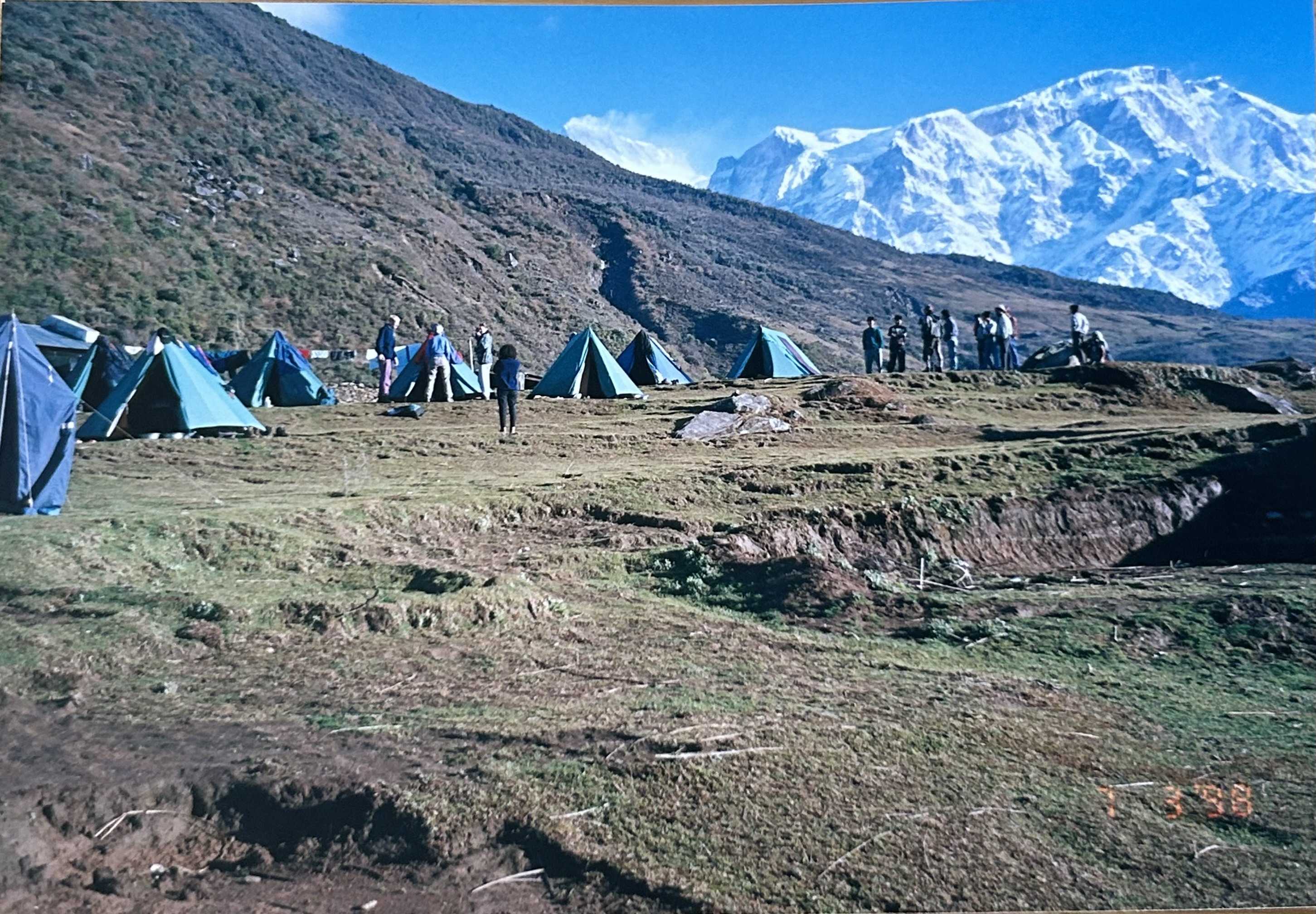

Over the next eight days our group, guided by the stoic Gomel and his fellow Sherpas, trekked a part of the Annapurna ranges, sleeping in tents, toileting in a hole in the ground, and eating the most unusual meals.

The only time we could wash was before each meal, when a metal bowl with Condys crystals and water was produced, for "washee washee" of our hands.

In those days my hair was long, and on the trek I kept it plaited and in a cap. After a few days I was desperate. I tried to wash it under a water spout on one of our village stops.

Every village had one. The water of course was freezing, the experience painful. But the Sherpas got a kick out of it. And I had clean hair again.

Because of the continued physical closeness, and the sharing of such a rugged experience, our group became firm friends.

There was Thomas Jefferson Deanes, our Appalachian mountain man, who told us all about a mysterious new scheme he used, and that we should take a look at, called Frequent Flyers.

At the time we were in awe, this was revolutionary. We could be interested in this.

Young Tom and Sian,in their mid 20s, were student doctors travelling from London. They succumbed to travellers diarrhoea very early on in the trek, having had a bout in India beforehand. They were valiant as they soldiered on and set their tent closest to the latrine.

Carol No.2 and her girlfriend had done absolutely no training for what lay ahead, and quite soon suffered as a result. There is virtually no level ground on that trek - it's climbing up or down. So every afternoon, hubby offered his massage services to the group and was very much in demand.

There would we all have been without the amazing Jean from Adelaide, 74, grieving for her recently deceased partner, and on a mission to find herself spiritually.

Jean was enigmatic, kind,and defiant. We were all told not to drink yak’s milk if offered to us as a gift by the locals. Jean did and thrived. Locals loved her. She was always the last to arrive at any given camp - it was a youthful group, and we were happy to get a rest while waiting for her. Two Sherpas walked with her and she always smiled.

Our Sherpas not only carried our tents and bedding, but also prepared the meals, and often provided spontaneous fun. We learned their Nepali dances and danced with them.

We listened to their songs but by far, their favourite thing was to discern very early on, who had a problem with heights or swaying bridges, and then to play a little trick. No prize for guessing their favourite prey - me, of course.

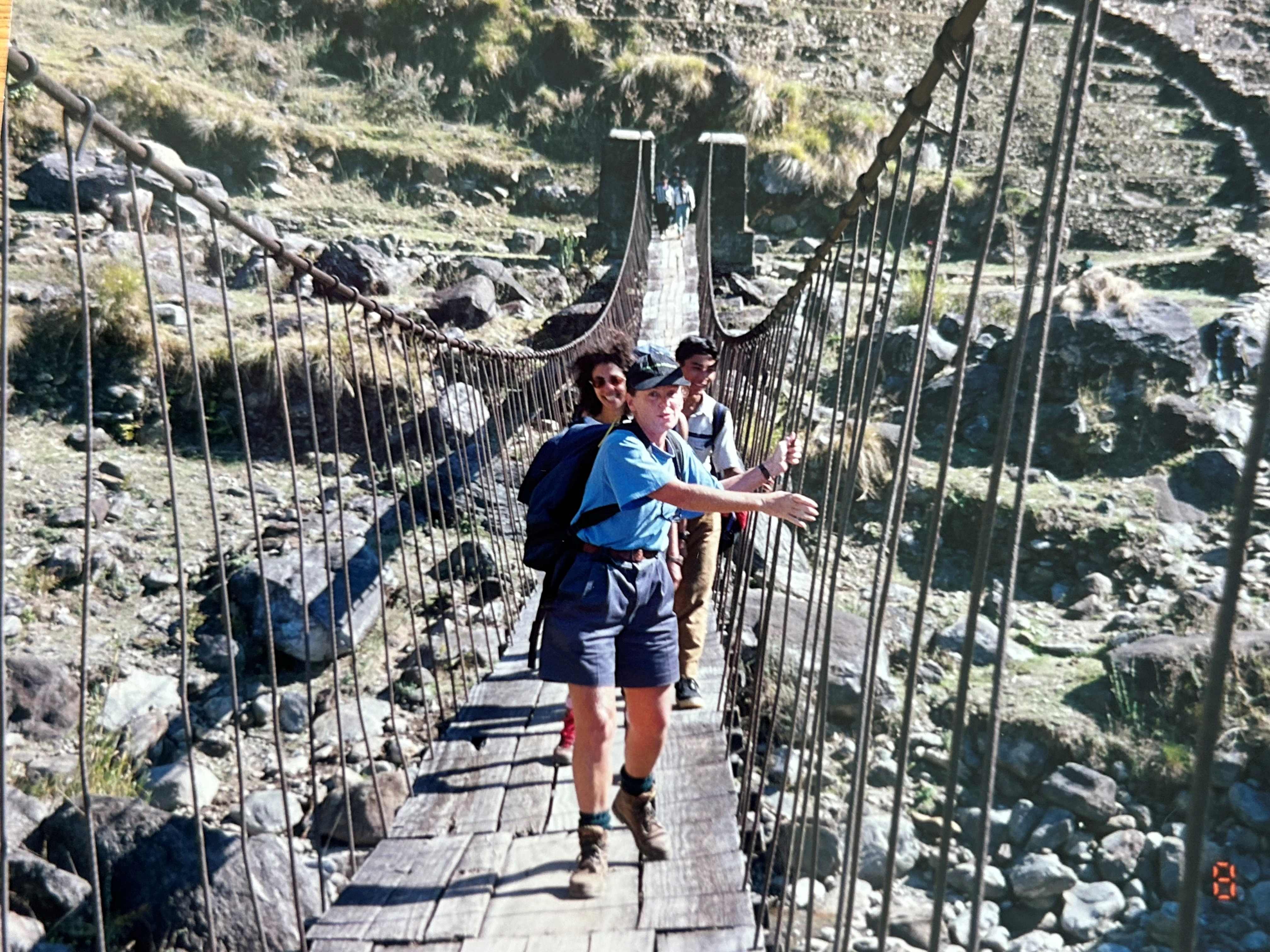

One of my stipulations to hubby before even choosing Nepal, was "no rope bridges please - make sure you check before we book".

And 10 minutes into our first steps of the opening day, there it was: a set of rickety timber poles lashed together with fibrous rope, the poles individually twisting this way and that, bridging a rapidly flowing river. And, even worse, we had to cross it one at a time.

Feeling faint and with heart in mouth and a resolve to strangle hubby if I survived, off I gingerly walked. Got to nearly the middle when one of the Sherpas in his thongs ran up behind me, purposely swaying said bridge. Much to the delight of all watching.

This was my baptism of fire. I survived. And over the next eight days bravely took those bridges on, at the end almost fearlessly.

There was no such thing as OH&S on this trek. We walked along tight paths cut into the side of hills so high - the gravelly paths often slick with rain.

The dropo-ffs into certain oblivion below were heart palpitating to look at. And we were starting most days in T-shirts and ending in thermals and ponchos, given the changes in altitude and temperature.

Then there was the delight of arriving in villages, sometimes stopping a while and meeting locals, and lots of children, who found us quite fascinating.

Namaste was always the word said, with prayer hands and a smile.

On we trekked, clambering over river stones in fast moving, icy water. We were climbing endlessly. Our knees let us know when we were descending.

One afternoon, we tramped through Rhodedendron forest, which was pristine, ancient and spiritual in the fading light.

It was a salve for the senses. We were to camp here overnight, but it wasn't to be. We needed to move on.

The guides had heard that tent slitters were in the vicinity, further ahead along the trail. They worked in the dark of night, slitting your tent and grabbing whatever they could. So we left, to walk yet another hour as dusk descended.

On each day of our trek, there appeared to be a local jungle telegraph happening.

Wherever we walked, young boys would emerge from the forest carrying buckets with iced drinks, usually Coca-Cola or Pepsi or beer, sometimes little flasks of rum or whisky, and chocolate bars, all available at a price.

In the trekking months, it provided them with a constant income.

One such boy we befriended. His name was Mon and 12 years old. He followed us, and we noticed he had a severely infected big toe. Thomas offered to clean it up. We bandaged it. I gave him my bandanna.

The next day Mon appeared with his drinks, no bandage to be seen, no footwear, but still wearing my bandanna.

Life is very hard in the mountains, and these people, because of their isolation, have developed a strength and resilience we in the West can only dream of.

They survive in the toughest of conditions. And appear to glow with health, despite the occasional sore toe.

Mon took us to his house to meet his parents. It was a mud house with shelves cut into the mud walls, and their meagre possessions,utensils, pots, plates and pans were placed on these shelves . In the middle of the only room was a fire pit, and around it were sleeping bunks.

We were graciously welcomed and it was an unforgettable experience. As neither we nor Mon’s parents could communicate verbally, body language was mostly how we connected.

There were smiles and Namastes all round.

Outside on the wet and muddy streets, yaks wandered aimlessly and water flowed down the sides of the road, but the air was so crisp, the sky so blue and the mountains so magical.

I could now fully understand why mountaineers and climbers do what they do, despite the dangers. Nepal gets under your skin - even when you are tired and aching, you love the challenge.

We had trekked from temperate rainforest up to the snow line, traversed raging rapids and met countless locals. Wwe had laughed, pushed ourselves physically and mentally, helped each other and learned so much about ourselves along the way.

It was my trip of a lifetime.

NEWS