The stories we tell about dying can change how we live.

Lynne Strong

14 May 2025, 8:00 AM

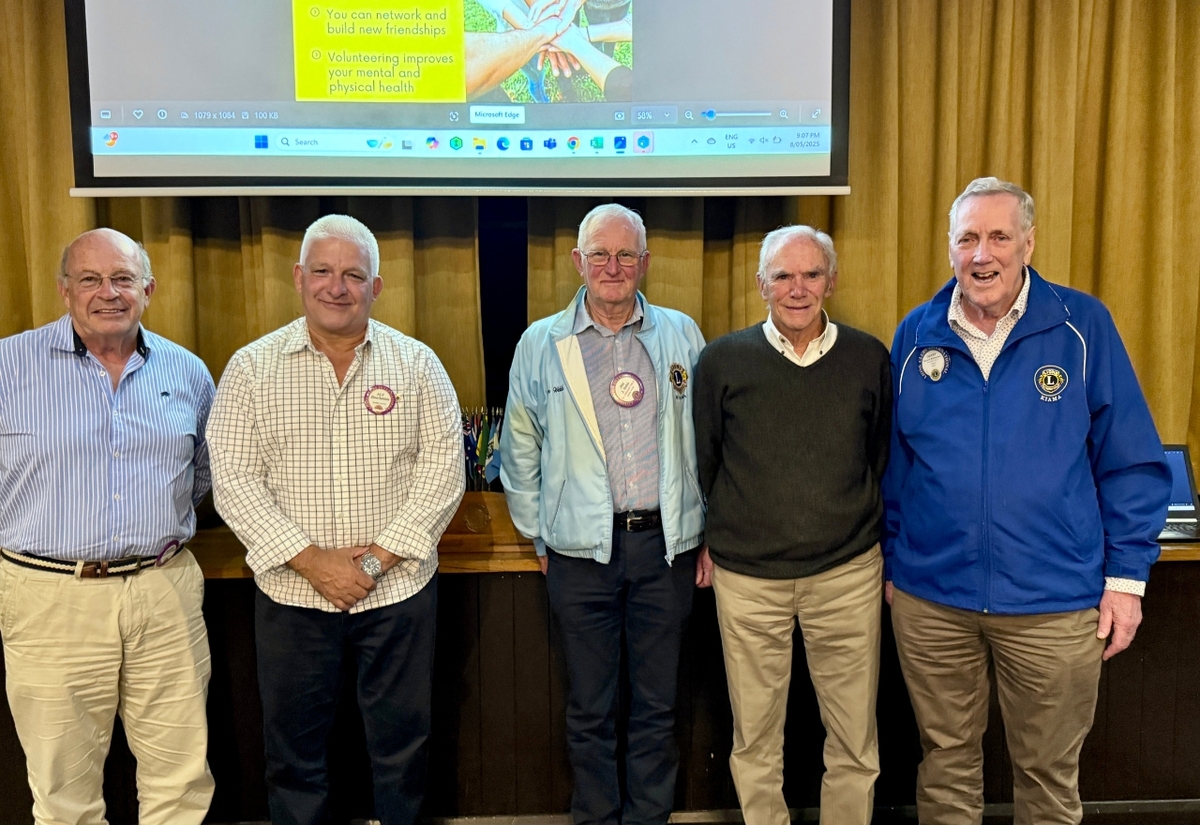

Lions Club of Kiama members gathered for a special evening with guest speaker Dr Michael Barbato. From left: Dr David Grant, new inductee Alf Bartolotta, Club Secretary Jim Webb, Dr Michael Barbato and Gerry McInerney.

Lions Club of Kiama members gathered for a special evening with guest speaker Dr Michael Barbato. From left: Dr David Grant, new inductee Alf Bartolotta, Club Secretary Jim Webb, Dr Michael Barbato and Gerry McInerney.It was a full house at the Lions Club dinner on last Thursday, but the room fell into deep, thoughtful silence as retired palliative care expert Dr Michael Barbato took the floor.

He brought a presentation that was anything but ordinary. His slides were simple, elegant and powerful, drawing the room into the quiet truths we often avoid.

As one attendee remarked, “He could teach a masterclass in how to use slides.”

Introduced by local GP Dr David Grant, Dr Barbato delivered a message that was both confronting and comforting.

None of us want to die, but there is a better, kinder way to do it.

He began by addressing the silence that often surrounds death. “We talk politics and religion,” he said, “but not dying.”

It is a reticence he understands but believes our communities must face. “Telling the truth hurts,” he said, “but deceit hurts even more.”

Among the many stories he shared, one stood out - author Cory Taylor’s reflection that the worst part of dying was not the pain, but the loneliness.

In her final book, Dying: A Memoir, Taylor wrote not of fear or agony but of a disconnection from those around her, who often did not know how to simply be present.

Dr Barbato described how, just 70 years ago, most people died at home, surrounded by family. Today, medicalised death can too easily isolate people at the exact moment they need connection most.

That is why the emergence of End-of-Life Doulas, now a formally accredited service, is so important. These doulas advocate for the dying, supporting them and their families in navigating options, emotions and care.

The key, he stressed, is comfort. “When people are in pain, all their energy goes to their body. Only once they are pain-free can they begin to deal with the emotional and existential reality of dying.”

Then came the heart of his message - End-of-Life Visions and Dreams.

These vivid, often symbolic experiences happen not in delirium, but in clarity. They are not hallucinations. They are gifts.

A woman who saw her bags packed and a boat waiting, though no one had told her she was dying.

A mother visited in a dream by her own late mother. A young man who saw a figure named Trent sitting on a chair by his bedside.

A little girl gazing out the window and smiling moments before she passed.

These are not rare, Dr Barbato explained. “They occur in 80 to 100 per cent of dying people.” They bring peace, open conversations and often allow for reconciliation and final expressions of love.

But loneliness, he warned, still haunts the dying. Too often, visitors arrive with what one patient called coffin eyes - full of sadness and fear, unable to meet the moment.

“The job of visitors,” he said, “is simple: Show up. Shut up. Listen. Be the friend you have always been. These people are living, not dying.”

And truth telling? It does not mean announcing the end. It means giving people space to talk about dying, if and when they are ready.

“If they are not speaking of dying,” he said, “they are not in denial. They are handling it the best way they can.”

Dr Barbato closed by sharing his own near-death experience at age seven, and the moment he witnessed a dying patient sit bolt upright, arms outstretched, in a vision just minutes before she died.

His final message was clear.

The dying do not need pity or performance. They need presence, permission and peace.

FACES OF OUR COAST