Tales of old Gerringong: Billy Lees the blacksmith

Local Contributor

16 June 2025, 1:00 AM

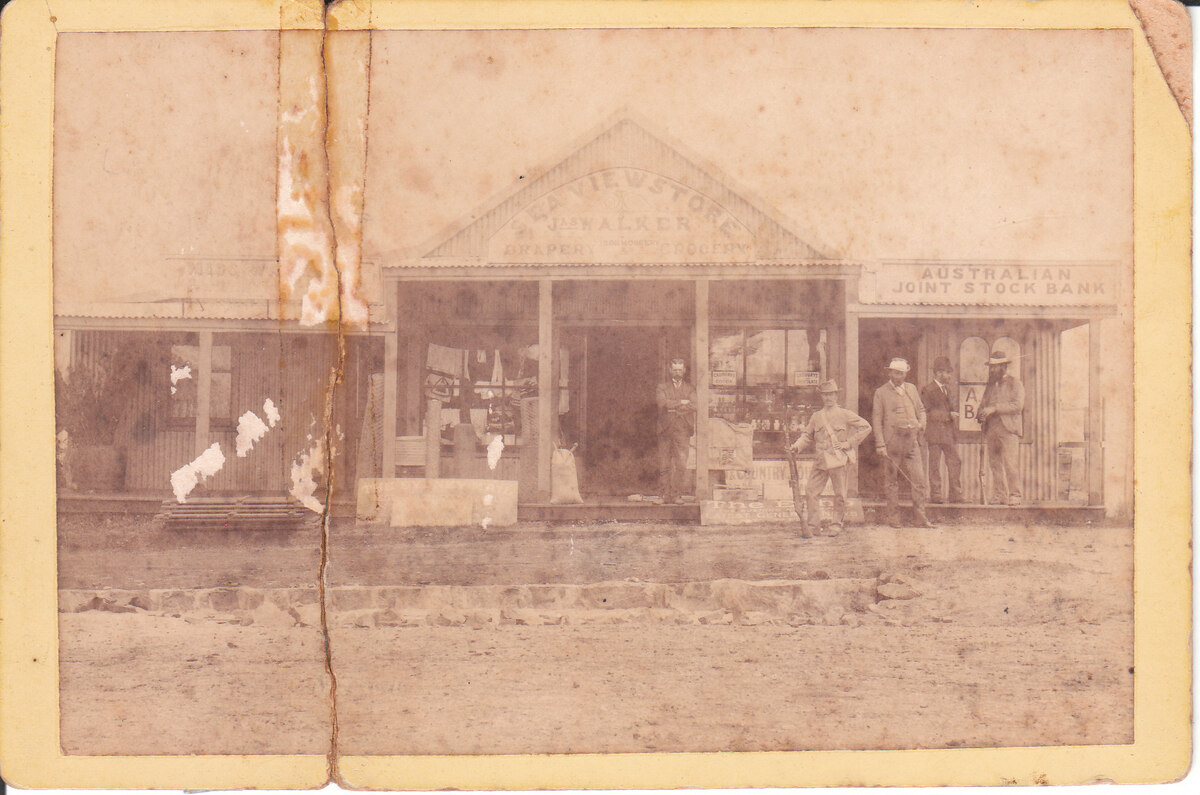

A store in Gerringong opposite the Town Hall around 1900. Photo: The Emery Family Collection

A store in Gerringong opposite the Town Hall around 1900. Photo: The Emery Family CollectionBy Clive Emery

Blacksmiths were such an essential part of the community more than a century ago, especially in country areas. Before tractors, cars and trucks, horses would do most of the work. Clive Emery brings to life the story of one in Gerringong, Billy Lees.

Billy Lees was one of four blacksmiths we had in Gerringong, from early in 1900 to about 1950. Other names were Cockerill, Bourke and Fitzpatrick.

Billy's shop was in Fern Street where the old Post Office building (now changed to commercial enterprises) was situated. I well remember turning the handle of the bellows for him while a horseshoe was being softened for shaping in the bed of coke or coal simmering in the bed of ashes.

This was contained by brickwork against the northern wall of his corrugated iron premises.

There was a sign painted on the outside of the southern wall of the building, which was displayed in blue lettering and read, for as long as the premises remained: “Dr. Morse's Indian Root Pills.”

As a boy I thought it was some remedy for ailing horses, because Billy was also a horse doctor. I knew this because he came to our farm at Crooked River once to dose one of our horses suffering from gripes.

The remedy, as I remember, was a bottle of whisky. The horse was up and about within the hour!

There are many things for which Billy should be remembered besides shoeing horses. The principal one was his eternal good humour. In all my life I do not remember meeting him in anything but a cheerful mood.

Billy was a nugget of a man whose strong, hairy arms were never covered.

He wore a short-sleeved flannel shirt open at the neck and heavy tweed trousers with a bluish tinge.

He had a breaking-in yard on the boundary of the school ground where we could watch him breaking in horses for the farmers.

Two sons, Tommy and Tod, would be helping on most occasions, especially if a horse was to be broken to the saddle.

The Walker residence Gerringong, where the chemist is now. Photo: The Emery Family Collection

Young Tod did this job in the circular yard. Tod was a great horseman and as a young man, worked in Neely's store, riding around the district taking orders each Monday, and delivering them in a sulky the next day.

Tommy was the elder of the boys and worked on the roads mostly during his period in Gerringong. Tommy had bright blue eyes like his father and remained an excellent citizen during his lifetime in Gerringong.

Billy was to be found in his pole and corrugated iron premises on most days, and the “ring” of steel as he hammered shoes into shape and mended broken machinery and plough shares for the farmers could be heard all over town.

On most days, if they were “shoeing days”, the smell of burning hooves was abundant as red-hot shoes were temporarily fitted and shaped the hoof rather than the reverse, to be then cooled and refitted.

He had room in the shop for three horses at a time, and most farmers waited for the job to be done, when the horse would be put back in the shafts and driven home.

Everyone in town knew when it was “shoeing day”, for the mixture of coal fire and burning hooves floated before the breeze.

However, shop doors were never shut as a result, for Billy was as much entitled to free trade as anyone else, and respect for him as a person and a worker would be far too strong in any case.

Billy had a daughter, “Bubby”, who attended the school as her brother had done, and for a period when I was a student.

She was slight of build and wore her hair shoulder length. She and Ella Donovan were neighbours as well as great mates.

His wife was a great worker for the Anglican Church but otherwise was content to care for the home beside that of the Donovans.

Billy's shop was a Mecca for idle men. When Tom Love retired from dairying to Fern Street he would always be found at the shop, helping Billy by turning the bellows handle if it was necessary while Billy shaped red-hot shoes and punched seven holes for the nails.

Great yarns were told and retold, when Tom pushed the old wooden window out and propped it with the swinging shaft to keep it stable and sat on a block at the aperture to watch the traffic.

Perhaps a cart or two or Jim Donnelley delivering a passenger to his destination with his coach and pair, or perhaps he might spot James Walker looking out his shop doorway for a sighting of an approaching customer.

Billy and Tom were a great combination - they pondered, proposed and predicted between yarns and hammer blows, even while Billy was shoeing a horse with six nails in his mouth as he hammered the first one home!

Now they are gone forever! The shop has gone, the smell of burning horsehair has gone, and the ring of steel on steel will never again be heard in Fern Street.

The present has overtaken the past, as time goes by, taking the local smithy with it.

My personal interest in Billy as a young child was because he was the first man I had ever seen with gold in his teeth clearly visible when he smiled, as he did often, and I thought him a rich man.

The one thing in which he was rich was heritage, because his grandfather arrived on our shores in 1822, and his father settled in our district on a farm near the foothills of Willow Vale. Billy died in 1953, aged 72.

This article is from the archives of Gerringong historian Clive Emery.

NEWS