Community warns Kiama’s housing plan ignores basic infrastructure

Lynne Strong

29 April 2025, 6:00 AM

Dr Tony Gilmour and Housing Trust CEO Michelle Adair

Dr Tony Gilmour and Housing Trust CEO Michelle Adair You could feel the frustration in the room, not anger for anger’s sake, but a deep weariness that came from years of seeing housing decisions made without listening to the people who live here.

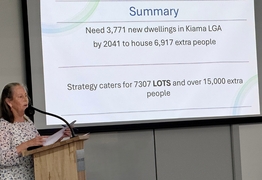

At last week’s housing forum at Kiama Leagues Club, the panel had spoken.

Then it was the community’s turn. What followed was part town hall, part truth-telling session.

So what would actually fix the housing strategy?

When the question was put to the panel they didn’t hold back.

Former urban planner Tony Gilmour suggested two quick changes: add affordable housing to the list of strategy priorities and make it crystal clear that in-fill and brownfield development are preferred over sprawl on greenfield sites.

"That’s planning 101," he said. "And we’re not even doing that."

Housing Trust CEO Michelle Adair called for data with a pulse.

“We need to know who’s going to live here,” she said. “How old are they, what are they earning, are they raising kids, are they care workers or casuals, or retirees?”

Without this, she argued, the strategy is planning for a place that may not even exist. She also called for an action plan with actual action, not vague “we’ll review this in two years” clauses.

Architect Madeleine Scarfe demanded targets. Social housing in the Kiama LGA sits at just 0.6 per cent - well below the state average of 4.2 per cent.

She also called for an increase to at least 5 per cent and for limits on short-term rentals. "Targets matter," she said. "Even if they’re modest, we need to know where we’re headed."

She also urged Kiama Council to take out Spring Hill and Riversdale Road from the strategy until demand justified it. “We don’t need them now,” she said. “Let’s not waste land just to hit numbers we don’t believe in.”

Bronwyn Siden, a retired town planner, spoke plainly. “You can’t achieve affordable housing in greenfield sites,” she said. “The infrastructure costs alone make it unviable.”

She called the current strategy a step forward, but one still fundamentally flawed.

Her message was clear: Council needs help. Volunteers, experts and locals must work together if the vision is to be realised.

Neville Fredericks, a developer and former Mayor backed her up. The real problem, he said, isn’t bad intentions, it’s bad regulation.

“The system is designed to produce sprawl,” he said. “If you want compact, walkable, diverse housing, you have to change the rulebook.”

And then came the big red flag - infrastructure. Or rather, the lack of it.

One long-time resident asked how 900 new homes could be approved without accounting for the waste they would produce.

He had done the maths: four people per home equals 720,000 litres of sewage from 900 homes per day. Has Sydney Water even been consulted?

No one could say. The silence was damning. “We’re already short on sewer and space,” he said. “We can’t keep piling people in and pretend it will sort itself out.”

Alan Woodward brought the cautionary tale. He spoke of Ligurano, a coastal town in Italy that once thrived.

Now it’s a ghost town half the year. Holiday rentals replaced families, schools shut down, and trains stopped running. “Could Kiama become the next Ligurano?” he asked. The room fell quiet.

And still, practical ideas kept coming. Bernadette Black, a South Precinct resident, described streets overwhelmed by short-term rentals - not a family getaway, but party houses for 18 guests with no development approval.

An environmental advocate warned that Spring Creek, Kiama’s last remaining coastal freshwater wetland, was under threat from proposed housing development.

A small local developer and builder stood up and told the story from the other side. “We want to build affordable homes,” he said, “but the system is stacked against us.”

He listed every layer of cost: stamp duty, capital gains tax, GST, land tax, holding costs and the endless risk of going to the Land and Environment Court. “We’re not the enemy,” he said. “We’re part of the solution, if we’re allowed to be.”

And yet, the room wasn’t cynical. It was clear-eyed. Create a citizen jury. Attract real innovation. Invite funders, insurers and housing organisations to collaborate with local knowledge.

“The innovation won’t come from Council,” said panel member Jacqueline Forst. “But it can come from us.”

In the final moments, 21-year-old Jordan Casson-Jones took the mic again. “If teachers and nurses and firefighters can’t live here, then this won’t be a community anymore,” he said. “It’ll just be a place.”

NEWS